Trafficked Hondurans forced to sell drugs in San Francisco is a myth

District 6 Supervisor Matt Dorsey wants the ability to seek deportation of fentanyl dealers — his fellow supervisors toed the tired Chesa Boudin line

“These people are victims of labor trafficking. They are told there are construction jobs in the U.S., then they are trapped and told if they don’t sell drugs the gangs will hurt their family members...”

— District 9 Supervisor Hillary Ronen on a proposal to seek the deportation of undocumented immigrants arrested for selling deadly fentanyl

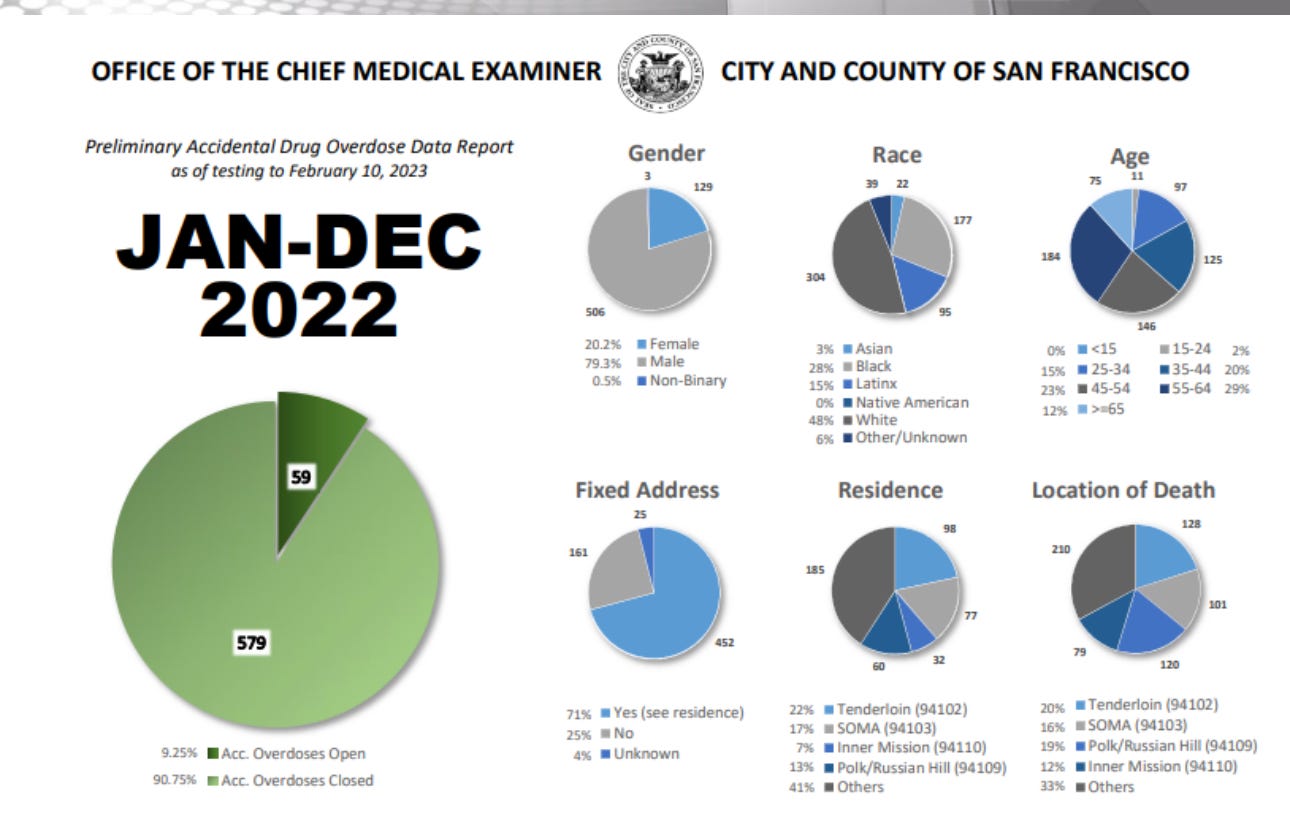

In 2022, there were 620 drug overdose deaths in San Francisco, 72 percent of which involved the highly potent synthetic opioid fentanyl. In January, 62 people died of overdose deaths, which puts the City on track for 682 more in 2023.

Nearly 70 percent of those 2022 drug overdose deaths happened in four districts under four members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors:

20 percent in the Tenderloin (94102) — District 5, Supervisor Dean Preston

19 percent in Polk/Russian Hill (94109) — District 3, Supervisor Aaron Peskin

16 percent in SoMa (94103) — District 6, Supervisor Matt Dorsey

12 percent in the Inner Mission (94110) — District 9, Supervisor Hillary Ronen

33 percent in “other locations”

Despite these horrific statistics, Matt Dorsey, a recovering drug addict himself, is the only supervisor to call for the deportation of fentanyl dealers. His proposed legislation, announced in a Feb. 14, 2023, press release, would “create a new exception to San Francisco’s sanctuary city policies for adults who have been convicted of a fentanyl-dealing felony in the prior seven years, and then held to answer for another fentanyl-dealing felony, a violent felony, or a serious felony subsequently.”

The change would allow local law enforcement officials to honor civil immigration detainers from federal authorities in narrow circumstances “to reflect the gravity of a crime that currently claims more than nine times as many lives as homicide in San Francisco, and that has been solely responsible for nearly three-fourths of all drug overdose deaths citywide since 2020.”

While many San Franciscans, who see the fentanyl carnage before them on a daily basis, vocally approved of the proposal, the other 10 supervisors did not. Even District 4 supervisor Joel Engardio, who ran on a “tough on crime” platform to oust incumbent Gordon Mar, didn’t back Dorsey. Nor did District 2 supervisor Catherine Stefani, a former prosecutor known for taking a strong position supporting the recall of former district attorney Chesa Boudin, who saw fentanyl dealers as victims. Siding with her colleagues, Stefani robotically spoke of the importance of the sanctuary law, “which allows victims of serious crimes to feel safe to go to law enforcement.” (That toe-the-line tone could have something to do with Stefani’s plan to run for the state assembly seat currently held by Phil Ting when he terms out in 2024.)

DEALERS ARE THE REAL VICTIMS

At a virtual town hall held July 25, 2020, then district attorney Chesa Boudin told a stunned audience that prosecuting drug cases came at too steep a price — for dealers. “A significant percentage of people selling drugs in San Francisco, perhaps as many as half, are from Honduras, and many of them have been trafficked here … we need to be mindful of the impact our interventions have. Some of them have family members in Honduras who have been or will be harmed if they don’t continue to pay off the traffickers who brought them here.”

Boudin then illustrated his point with a story. “I can tell you from a young Honduran man who I personally represented when I was a public defender, who was accused of selling drugs, and who was guilty of selling drugs, and who eventually plead guilty to what he was accused of … years before I met him, when he cooperated with federal authorities in a different state, his father in Honduras was killed in retaliation.” Boudin offered no details (for example, if the man’s father was killed because he cooperated in another state, why was he in San Francisco years later still selling drugs?). Instead, he used the anecdote to highlight why he believes drug dealers shouldn’t be sent to prison or be deported: “These are not idle threats, and we do not have the power to protect people in Honduras from these trafficking organizations.”

After Boudin went on the record, I asked five current and former Tenderloin district narcotics officers — involved in more than 4,000 dealer arrests collectively — about Boudin’s theory, who responded that they had never once heard a drug seller say they were trafficked. A recent search of San Francisco Police Department incidents since 2018 turned up only sex trafficking arrests.

Former San Francisco prosecutor Tom Ostly agreed. “I reviewed hundreds of narcotics sales cases. I never saw any evidence of dealers being involuntarily trafficked. I reviewed dealers’ social media, text messages, statements to law enforcement, and had countless conversations with affected community members. All evidence confirmed dealers were freely and enthusiastically engaging in the drug trade. One guy was making $20,000 a month and sending $6,000 home to Honduras,” Ostly told me. “Boudin claims to know people are being forced to sell drugs against their will. If that were true, then he has done nothing to protect them.”

The “family members will be harmed” pretext, according to Ostly, is a tactic used by the defense. “I had a case where the public defender said his client’s mom would be killed in Honduras — but his mom and brother were actually out in the hallway and had pending cases in Oakland.” And, Ostly said, if dealers were truly here against their will, they have a strange way of showing it: “They recruit people on Instagram. One guy filmed himself showing all the [drug] bindles in his mouth and flashing all the cash he was making. Of the 240 cases I reviewed pre-trial there was no evidence of trafficking, but there was lots of evidence of them making tons of money and loving it.”

THE MANSION THAT FENTANYL BUILT

In December 2020, a drug dealer who repeatedly ignored a stay away order in the Tenderloin was arrested four times in just 90 days. According to police, the defendant had three open cases and was caught with heroin, fentanyl, cocaine, meth, and cash. Earlier that same week David Anderson, then U.S. attorney for the Northern District of California, announced charges against the man, Emilson Cruz-Mayorquin, or “Playboy” as he was known on the streets, and seven members of his family and extended family, alleging that between July and December of 2020, they routinely traveled to the Tenderloin from Oakland to sell fentanyl, heroin, and other narcotics.

According to federal documents, despite being a mid-level dealer, Cruz-Mayorquin was the go-to person for fentanyl in the Tenderloin. On Oct. 29, 2020, he sold two ounces of fentanyl to a customer for $1,600. Later that day, agents intercepted a call to an unknown male about the sale, in which Cruz-Mayorquin says he just finished a “two-ounce deal with a new dude,” and that the gram customers refer other customers who purchase larger amounts. In other words, the drug addicts of the Tenderloin became a referral service, and it was very profitable.

During a call intercepted over the phone line of his mother, Leydis Yaneth Cruz, she speaks with a family member. “Life is a little stressed because Emilson has a lot of customers,” Cruz says of her son’s drug business. Then she moves on to the home he’s building in Honduras. “He’s removing the ceramic from the house; he’s going to put in porcelain — how can I say no to him?”

“That house is not going to look like a house, it’s going to look like a mansion,” the relative responds.

“My god, Emilson doesn’t stop spending, right?” Cruz asks rhetorically. “God permit … so there’s a mansion and a half.”

Exhibit photos display Playboy’s mansion in Honduras, replete with marbled bathroom walls and a porch held up by Roman-style pillars.

In December 2021, four months after pleading guilty to conspiracy to distribute fentanyl, Cruz-Mayorquin was sentenced to four years and three months in federal prison. In the sentencing memo, his public defender wrote that, after finishing his sentence, he will face the “ultimate punishment of banishment” through deportation back to Honduras.

When his mother was arrested in December 2020, agents seized nearly 1,423 gross grams of fentanyl, 153 gross grams of cocaine, and 276.5 gross grams of methamphetamine from the Oakland apartment she shared with her 4-year-old daughter, older daughter Pamela Carrero, and Carrero’s minor son.

On March 1, 2022, Carrero was sentenced to 19 months in federal prison. After serving her sentence, she will be deported. One month later, a judge sentenced Leydis Yaneth Cruz to three years and two months in prison, after which she will also be deported.

HYPOCRITE HILL’S HYPOCRITE HUSBAND

The night Boudin was recalled, Supervisor Ronen put on a performance for the TV news cameras worthy of a community theater production of Hamlet. Flailing her arms and sobbing, Ronen lamented the end of Boudin’s “progressive” policies such as his refusal to put “kids in cages” (no matter how heinous their crimes) and “not going after immigrants” (even if they build mansions with fentanyl blood money).

Ronen’s husband, Francisco Ugarte, who manages the immigration unit for the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office, went on a Twitter rant against the San Francisco Standard’s article revealing Boudin secured just three drug dealing convictions (for the lesser charge of “accessory after the fact”), and zero for fentanyl. In a bizarre twist, on May 20, 2022, the Standard bowed to the pressure and gave Ugarte a platform in a Q&A segment. “I’ve represented moms and dads ripped away from their kids, and teenagers who were trafficked here and then deported to their deaths. I’ve seen domestic violence survivors end up in deportation proceedings after they called police for help, and fathers permanently separated from their children after getting caught in the system,” Ugarte said. What he left out, however, is the way his own office uses immigration status against people.

In a 2017 San Francisco Chronicle column by Heather Knight, an undocumented housekeeper from Honduras named Maria said she called police in May 2015 to report being sexually assaulted. During the investigation and subsequent trial of the suspect, she said late Public Defender Jeff Adachi’s office used tactics so aggressive toward her that it exacerbated her trauma. They even interviewed her landlord, who then told Maria she had to move. “Adachi’s office included her full name, date of birth and immigration status in public court records,” Knight writes. “And in court, an attorney from Adachi’s office insinuated she was testifying only to try to obtain a type of visa available to crime victims.”

Court records obtained of several cases tried in San Francisco during Adachi’s years showed attorneys “regularly quizzed immigrants living here illegally about a special visa available to crime victims, apparently to cast doubt on their credibility. The attorneys have pressed their questioning about the visas, regardless of whether the alleged victim had applied for the visa and even if the victim testified he or she didn’t know about the visa when reporting the crime.”

Knight also discovered Adachi’s tactics were unique to San Francisco: spokespeople for the district attorneys’ offices in Alameda County and Santa Clara County said that “prosecutors couldn’t remember a case in which public defenders in those counties used such tactics,” and Michele Hanisee, president of the Association of Los Angeles Deputy District Attorneys, said she had not heard of the practice, calling it “pretty sleazy.”

Adachi, who mentored public defenders like Ugarte, was unapologetic about his tactics. “Part of what we do is investigate the motivations for a witness to make a claim,” he told Knight. “The idea that we’re somehow acting improperly in questioning witnesses about this is meritless … That’s doing our jobs as defense attorneys. It has nothing to do with my support of immigrant rights.”

THE REAL NUMBERS ON TRAFFICKING DON’T ADD UP

Despite mountains of evidence to the contrary, defense lawyers like Ugarte and politicians like his wife, Hillary Ronen, continue spouting the myth of trafficked drug dealers. “These people are victims of labor trafficking. They are told there are construction jobs in the US, then they are trapped and told if they don’t sell drugs the gangs will hurt their family members. … To go after the immigration status of people on the lower end of the totem pole attacks the sacred Sanctuary Ordinance,” Ronen said regarding Dorsey’s proposal.

District 7 supervisor Myrna Melgar, sometimes a wildcard on the Board, noted the Sanctuary City Law “also protects workers, for example day laborers, who may work for two weeks for a boss who then says they aren’t going to get paid—and if they complain, the boss threatens to call the cops and allege that they are drug dealers.”

Of course, San Francisco has perhaps the strongest Sanctuary City Law in the country, defining the violent felonies ineligible for sanctuary protections as any of the more than two-dozen crimes identified in California Penal Code Section 667.5(c), which includes murder, voluntary manslaughter, mayhem, rape, robbery, arson, attempted murder, kidnapping, carjacking, or threats to victims or witnesses. Other currently disqualifying felony convictions are for human trafficking, felony assault with a deadly weapon, or crimes involving the use of a firearm, assault weapon, or machine gun. Existing San Francisco law also defines serious felonies that are ineligible for sanctuary protection, which include violent felonies “as well as rape, exploding a destructive device with intent to injure, assault on a person with caustic chemicals or flammable substances, or shooting from a vehicle at a person outside the vehicle or with great bodily injury."

Most undocumented immigrants are law-abiding, hardworking men and women just trying to raise their families. Sadly, they often live in the very neighborhoods where gangs and drug dealers run the streets and are therefore most affected by the crime and violence that comes with the territory. Politicians like Ronen don’t stand up for these undocumented immigrants, who are the real victims of the fentanyl crisis.

Here’s another question for Ronen and Ugarte: If dealers are trafficked from Honduras to San Francisco and forced to sell drugs, why didn’t their ally Boudin prosecute the cases? And why didn’t Ugarte speak about the traffickers that his office represented, since that would be the job of public defenders like him?

The answer is likely because the numbers don’t add up.

According to the U.S. Department of State’s 2022 Trafficking in Persons Report: Honduras, the government investigated a total of 148 trafficking cases in 2021: “64 cases for sex trafficking and related crimes, five cases for forced labor, and 79 cases of unspecified exploitation.”

Forced labor victims included “22 women, 14 men, nine boys, six girls, and two LGBTQI+ persons whose gender and age were not specified.”

So, if the United States government identified a total of five forced labor trafficking cases involving 53 Hondurans in 2021, how many of those were fentanyl dealers in San Francisco? To find out, this week I sent a public records request to the San Francisco District Attorney’s Office, but I’m guessing the number is zero.

For years I’ve written about San Francisco officials and their sheep-like behavior on controversial legislation. When it comes to taking a hard line on deadly fentanyl dealers, they once again proved me right, with one exception. Politicians follow the herd while leaders are lone wolves. Right now, the only leader I see on the Board is Matt Dorsey.

At Mayor London Breed’s March 7, 2023, press conference urging the Board of Supervisors to approve a $27 million budget supplement for police overtime and recruitment, a few hecklers booed when Dorsey took the podium. “I make no apologies that I am fighting for the lives of drug addicts and not the livelihoods of drug dealers,” he responded. It’s a shame his fellow policymakers don’t feel the same.