Colleague on Jennifer Friedenbach: 'She doesn’t want to kill the goose that lays the golden egg'

Executive director of Coalition on Homelessness gets residency for out-of-state unhoused to ‘keep things the same’

My August “Reynolds Rap” column for the Marina Times newspaper (“Fraudenbach: How the Coalition on Homelessness is holding San Francisco hostage”) elicited one of the strongest reactions from readers I’ve ever received. One group of concerned citizens from various neighborhood organizations even took hours out of their busy lives to attend the August 3 Homeless Oversight Commission meeting, collectively reading the article word-for-word before its members (you can watch the video here). Unfortunately, the target of my exposé, Jennifer Friedenbach, was absent that day.

As I wrote in Reynolds Rap, former KTVU reporter Sara Sidner returned to “Gotham by the Bay” to delve into the city’s lethal cocktail of fentanyl and homelessness for a one-hour CNN documentary titled, “What Happened to San Francisco?”

When Sidner sat down with former mayor Willie Brown to ask why he believed San Francisco couldn’t make a dent in its catastrophic homeless problem, Brown was succinct, even smug: “It is not designed to be solved. It is designed to be perpetuated. It is to treat the problem, not solve it.”

Whether Sidner edited the piece purposefully or not, it was apropos that Brown’s comments followed an interview with Jennifer Friedenbach, executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness (COH), where she’s spent the last 25 years presenting herself as an expert on the subject.

What are Friedenbach’s qualifications? She doesn’t really have any. Her vague résumé includes a lot of fundraising and, prior to COH, serving as director of the Hunger and Homeless Action Coalition of San Mateo County. Her skill set, as thin as her résumé, touts “a long history of community organizing, working on a range of poverty-related issues including welfare rights, housing, homeless prevention, health care, disability, and human and civil rights.”

I’ve referred to Friedenbach as “CEO of the city’s de facto homeless marketing agency,” spending their money on Sharpies and cardboard to make the handwritten signs they hold up at City Hall protests, but one person who reached out to me had a lot worse to say about Friedenbach’s 25-year reign over San Francisco’s homeless industry. A longtime social work professional, he asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution. “Jennifer is known to be vindictive,” he said.

Nearly three decades ago, the social work professional (we’ll call him “Carl”) started his career as part of MultiCrisis, meeting the homeless population at night wherever they were staying, from parks to underneath bridges, to educate them about the dangers of dirty needles, and to encourage them to get tested for HIV. “Particularly with the gay Asian-Pacific Islander community, there was a hesitancy because they didn’t want to bring shame on their family,” Carl said during a phone interview. “In some cases, when someone passed from AIDS, the family would ask the doctor to change the cause of death from AIDS to pneumonia or another illness.”

From MultiCrisis, Carl moved into triage with San Francisco’s General Assistance program (GA), helping homeless individuals get stabilized and find housing. He’s spent 20 years with in-home supportive services, or IHSS. Funding for the program is split between federal (60 percent), state (30 percent) and the city (10 percent) but doesn’t cost taxpayers anything.

“Almost 50 percent of the homeless are single adults with no family, and most are from out of state,” Carl said. A person only needs to establish that they’ve lived in San Francisco for two weeks in order to apply for Supplemental Security Income (SSI), but the standards are stricter than most realize. “You have to have an actual address, not a P.O. Box,” Carl explained. “You have to show proof, like a PG&E bill.”

There is, however, one bypass for getting SSI without actual proof of residency: a letter from the Coalition on Homelessness written by Friedenbach. “Then the GA program doesn’t even question it,” Carl said. “Her letter is like a grantee loan certification from the program.”

Twenty years ago, when Carl and his colleagues started SSI GA, Friedenbach was establishing herself as a bright new star on San Francisco’s homelessness front, so they asked her to be part of their program: “We explained that when we help someone with the application process, it can take from two to five years to get approved.” Friedenbach declined the offer — until she realized the money involved. “After that long period of time, once the person does get approved, the check is sizable,” Carl said. “It can be anywhere from $10,000 to $20,000. When Jennifer saw the dollar amount, she wanted a piece of the pie, and suddenly she was interested in participating.”

“KA-CHING, KA-CHING!”

There were stipulations for the SSI GA program, including accountability on the part of participants. “Without accountability you have nothing,” Carl said. “We would get them into job training or the trades, or retrain them for something else if they had a disability that prevented them from using their previous skills.” As homeless programs go, SSI GA was a success, with approximately 50 percent of participants staying the course. There was also a social worker onsite at each of their buildings 24/7. If a resident was causing problems, or was dual diagnosed with mental illness and addiction, they had to leave the program and go into a rehabilitation facility. Friedenbach had a huge issue with that. “She said ‘You can’t force someone into treatment, they must be willing and make their own decisions,’” Carl recalled. “And I said, ‘If they were able to make their own decisions they wouldn’t be here!’”

Friedenbach saw things differently, so she began taking over the program and molding it to meet her own agenda. “She didn’t want to kill the goose that lays the golden egg,” Carl said. “Jennifer wanted to be the middleman. Instead of having the money go back to cover the program’s expenses so that it wouldn’t fall on taxpayers, she wanted a piece of the pie. She didn’t want to be involved until she heard the ‘ka-ching, kaching!’”

As Friedenbach’s influence grew, the program fell apart. “I left because of her bullshit, and within two years the program was gone because of her,” Carl said. “You called her ‘Fraudenbach’ [in the title of your article], but you’re being too kind. I call her the ‘homeless pimp.’ We stabilized their lives, she wanted to make money as their middleman. Even a lot of homeless people hate her because the Coalition takes a cut...”

In other words, Friedenbach and friends are making a fortune from the misfortune of others.

Today, Carl still works in social services for the City and County of San Francisco helping the homeless, as he has for nearly 30 years, and he says he’s glad someone finally exposed Friedenbach: “She’s a wolf in sheep’s clothing. She’s a liar. I’ve been trying to get people to listen about her for years … Every time we try something new Jennifer puts up a roadblock because she wants to keep things the same. She runs the homeless industrial complex. If you’re able to write a letter for someone who just arrived on a Greyhound bus and get them taxpayer money, you’re the CEO. All the mayors and all the supervisors have listened to her and now they’re afraid to speak out against her. But if she was successful, we wouldn’t have this problem. She’s been here so long and people think she does so much good, but they don’t see her evil side.”

LACK OF TRANSPARENCY

The Coalition on Homelessness is incredibly opaque in their 990 filings, required by the IRS to verify that nonprofits should keep their tax-exempt status. It’s no secret the IRS rarely audits these forms, particularly for smaller organizations, but 990s should provide an overview of nonprofit revenue, expenses, assets, and liabilities, as well as sum up the group’s mission, indicate who sits on its board of directors, and state the highest-paid employees’ pay.

The COH mission statement tells you what the rest of the 990 will look like (and that they need to hire a copy editor). “Our vision of our city is where housing is a human right where homelessness is only ever temporary and dignified and where those are forced to remain on dignified and where those are forced to remain on…” it rambles and repeats. (And yes, those are the exact words.)

Charity Navigator won't even rate COH, in part because the organization doesn’t track their results. “Ratings are calculated from one or more beacon scores. Currently, we require either an Accountability & Finance beacon or an Impact & Results beacon to be eligible for a Charity Navigator rating,” the website explains.

According to their IRS filing for 2019 the total assets of COH grew from $400,000 to $1 million. Friedenbach classified her entire salary as "political campaign expenditures" to avoid showing it as a separate compensatory line item. If you read the supplemental information, everything COH did was "advocated, fought, called attention to…" Basically, they spent $610,000 to harangue policymakers and critics, and $60,000 on “programs.” (They also spent $42,000 on someone's relocation expenses, but there’s no explanation as to who was relocated or why).

For 2021, COH lists salaries, other compensation, and employee benefits as $487,511, with 10 people receiving the title “Individual Trustee or Director,” but the only salary goes to Friedenbach (a paltry 50,340 annually). There are no other employees listed in the filing, so where did the other $437,171 go? Your guess is as good as mine. The 2021 annual report contains numerous typos but no financial disclosures. The operation appears set up to do as Friedenbach pleases with little to no scrutiny.

WAIVER OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Also suspect is Friedenbach’s seat on the “Our City Our Home” oversight committee. In 2018, COH drafted a plan to raise $300 million a year for “homeless services” by increasing gross receipts taxes 0.5 percent on San Francisco businesses making more than $50 million annually. They chose Christin Evans, a longtime homeless activist who runs hobby businesses in the Haight-Ashbury district and whose parents own a $12 million home in the city, as their unlikely spokesperson — but it paid off for COH in more ways than one.

While scrolling through Twitter, Evans came across a post from Marc Benioff, the founder and CEO of software company Salesforce, referring to San Francisco as the “Four Seasons of homelessness.” Outraged, she tweeted back, “Did @benioff just compare SF’s homeless services to a luxury hotel chain? How out of touch can a billionaire be?!?!”

Intrigued, Benioff reached out to Evans and the two exchanged private messages. While Benioff attributed the quote to somebody else, Evans saw an opportunity to reel in the CEO of San Francisco’s largest employer.

By the end of their chat, Benioff supported the measure, despite the fact it would cost his own company millions. He and Salesforce donated a combined $8 million to the campaign (the most ever spent on a local ballot measure so near to election day). Benioff became Prop. C’s biggest champion, chastising fellow CEOs for “not caring about homeless people.” Even his celebrity friends, comedian Chris Rock and singer Jewel, came onboard, shooting endorsement videos for Evans and COH. “We call her the CEO whisperer,” Friedenbach boasted at the time.

It took a couple of years to wind through a court challenge from the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, but in June 2020 the funds were released. Swelling to $600 million by 2022, the city spent only a quarter of that amount.

According to SF.gov, the Proposition C oversight committee for “Our City, Our Home” (OCOH) makes sure spending from the fund is “fair and accountable,” however, OCOH is one of the least transparent city programs I’ve seen — and that says a lot. While Friendenbach has claimed for decades that COH doesn’t take city money, they’re taking money from OCOH in the form of a $250,000 grant. Friedenbach is also CEO of OCOH, and sources tell me it’s Friedenbach who “runs the show.” The website’s word salad, riddled with typos, says COH earned the grant because they “prepared testimony and trained presenters to testify before City Budget decision-makers, both in the Office of the Mayor and the City’s Board of Supervisors.”

In May, when I questioned Friedenbach on Twitter about what appears to be an egregious conflict of interest, she abruptly deleted her account.

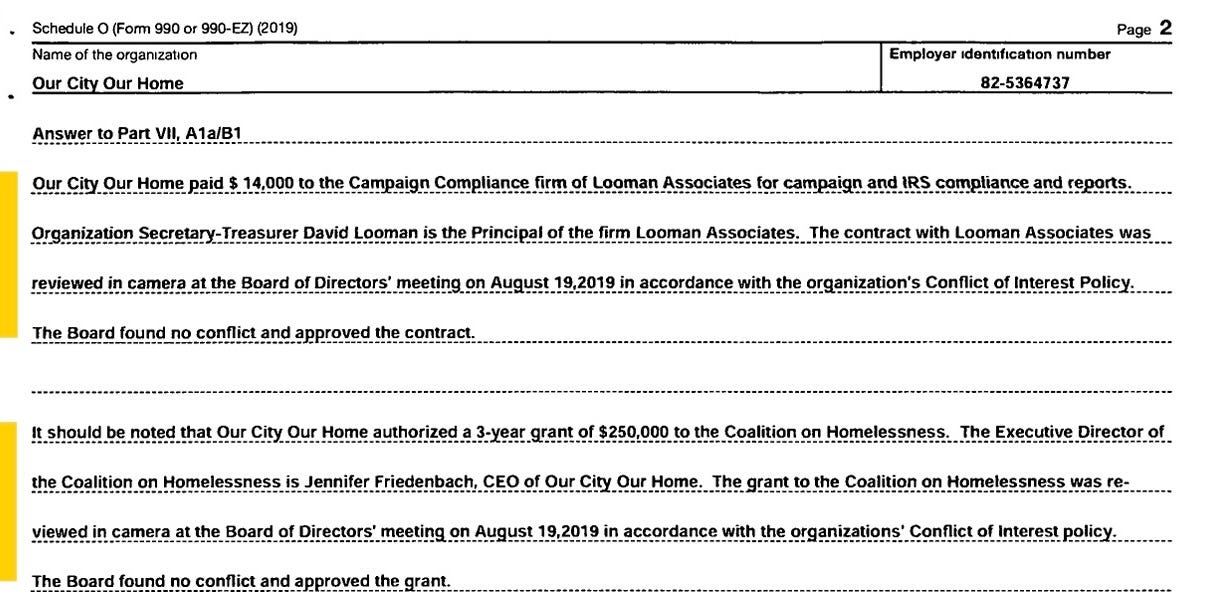

So how is Friedenbach able to pass a grant from OCOH on to her personal homeless organization? An examination of the OCOH 990 form for 2019 shows that the committee authorized the grant and waived any conflict of interest: “It should be noted that Our City Our Home authorized a 3-year grant of $250,000 to the Coalition on Homelessness. The Executive Director of the Coalition on Homelessness is Jennifer Friedenbach, CEO of Our City Our Home. The grant to the Coalition on Homelessness was reviewed in camera at the Board of Directors' meeting on August 19, 2019 in accordance with the organization’s Conflict of Interest policy. The Board found no conflict and approved the grant.”

You read that right: the Our City Our Home Oversight Committee found no conflict of interest with CEO Jennifer Friedenbach granting her own nonprofit, The Coalition on Homelessness, a quarter of a million bucks.

FIELD OF PIPE DREAMS

So how is the money being spent? That has Friedenbach written all over it, too. OCOH budgeted $390 million for “permanent housing” and just $53 million for “shelter and hygiene.” Friedenbach is an adamant proponent for “permanent housing,” but she has never offered a plan for what that looks like in the real world.

Even if anti-housing supervisors like Dean Preston suddenly approved $400 million worth of units on an abandoned Nordstrom parking lot where they cast shadows one day a year, and even if the city could buy existing properties or build new ones in a Barbie Dream House timeframe on steroids, would taxpayers be on the hook in perpetuity while the formerly homeless live rent free, doing as they please?

Then there’s the Field of Dreams analogy “If you build it, they will come” — after San Francisco houses the estimated 4,400 people now on the streets, what happens when more show up?

If sounds like Friedenbach doesn’t really want to solve this issue, there’s more: In September 2022, COH helped seven homeless individuals file a lawsuit alleging San Francisco violated their rights by “punishing residents who have nowhere to go” when removing tents and belongings from public spaces, with the goal of forcing the city to spend billions more on “affordable housing and other resources.”

U.S. Magistrate Judge Donna Ryu later agreed, granting an emergency order based on “evidence” presented by COH that the city regularly violated its own policies when clearing people from encampments without offering adequate access to shelter, which, in California, is illegal.

In July, San Francisco City Attorney David Chiu fired back with a motion in U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California refuting allegations made by COH. “Instead of working through minor issues with the city, Plaintiffs have spent months unjustifiably painting San Francisco as a violator of people’s rights. Despite the superficial heft of Plaintiffs’ nearly 400-page filing, their factual assertions fall apart.” Chiu wrote. “Since the injunction was issued, the Plaintiffs have not identified a single instance of San Francisco citing or arresting someone under any of the enjoined laws. Unhoused people regularly refuse the city’s offers of shelter. For example, one plaintiff has been offered shelter multiple times, including an offer to live in an individual ‘tiny home’ cabin, which is typically considered a preferable shelter placement. But the plaintiff said he would have to check with his lawyers and then eventually refused the shelter space.”

The Robinhood of homelessness and her merry band of activists are also responsible for an appeal against the city over so-called “poverty tows,” which they claim harm low-income individuals, and the California Court of Appeal recently agreed. Towing cars that have accrued unpaid parking tickets without a warrant is a common practice in many cities, including San Francisco, where “legally and safely parked cars with five or more unpaid parking tickets” were towed if the owner didn’t respond within 21 calendar days of issuance. Knowing the Friedenbach playbook, however, this is just another tactic to ensure the homeless living in cars and RVs can remain parked wherever they choose, legally or not — even in front of your home or business.

To many of her critics, Friedenbach is nothing but a fraud, sitting on the oversight board of OCOH, created by legislation she was instrumental in passing, while accepting a $250,000 grant for her own nonprofit to prepare testimony and train presenters to influence decision makers. OCOH is pushing millions toward Friendenbach’s “permanent housing for all” pipe dream at the same time COH is suing the city for not offering enough shelter.

With conflicts galore, it’s time for Friedenbach to step down from OCOH. It’s also time for officials to stop listening to Friedenbach about the homeless crisis — after 25 years of big talk, her lack of success is visible each and every day on the streets of San Francisco.

You can read the “Our City Our Home” 2019 IRS Form 990 “With Highlights” in its entirety here:

Dyer should receive an immediate and substantial honorarium from the budget analysts’ or comptroller’s office for doing their job for them.

I agree that J Fried should be relieved of her office at OCOH. I also think that we have to demand that funds for OCOH be used to create enough shelter beds to house all of the unhoused people so that the city can begin to move people into more controlled shelter settings with services not available on the streets. Finally, we need to know who are on our streets and in our shelters for. Security purposes and so that we are not duplicating services.