Chesa Boudin sent hundreds of violent offenders to diversion — and he has no idea where they are

Two studies show programs were in deep trouble years before Boudin took office

In July of 2020, California Policy Lab (CPL) released a study entitled “Alternatives to Prosecution: San Francisco’s Collaborative Courts and Pretrial Diversion” to report on the city’s various diversion programs. The study addressed recidivism after diversion, new arrests during diversion, and the success rate of the programs. CPL is a nonprofit funded in part by Arnold Ventures (the foundation of billionaire and former Enron energy trader John Arnold) which also funds San Francisco’s Pretrial Diversion Project (PTD) and supports its goals.

Since the reviewing agency and the reviewed programs are both supported by Arnold Ventures, the inherent conflicts of interest makes it plausible that CPL might ignore or understate some of the problems they discovered — something to keep in mind when considering their conclusions. The report analyzed diversion outcomes between 2008 and 2018, and the key takeaway is that prior to Chesa Boudin becoming San Francisco’s district attorney in 2020, diversion and the collaborative court programs were already in deep trouble. In fact, even historically more successful PTD for low-level offenders was experiencing record failure rates.

Those diverted, especially for felonies, had higher recidivism rates than those who were never diverted

According to the study, cases referred to diversion had lower conviction rates than non-diverted cases, but referred individuals had higher rates of “subsequent criminal justice contact.” The lower conviction rates were expected since successful completion of the program results in dismissal of the charges.

What was unexpected is that diverted defendants had higher rates of subsequent criminal justice contact than those who were not diverted at all — the opposite of the intended effect.

As the authors explored potential explanations for the poor results, they noted that San Francisco is unique to most other jurisdictions. A national survey of prosecutor-led diversion found that as of 2017, only half of the programs were accepting individuals charged with felonies, and just one-third accepted individuals with prior felony convictions. Many of San Francisco’s programs serve individuals with multiple felonies and long criminal histories.

While referrals to PTD are similar to Collaborative Court referrals, and can be made “at any point during the case process,” most low-level offenders are automatically referred to PTD. When San Francisco’s program started in 1976, only first-time misdemeanor arrestees were eligible. Today, PTD is one of the largest programs but, according to the study, it is also “one of the least intense in terms of program requirements,” with participants often taking just a single educational course or community service assignment.

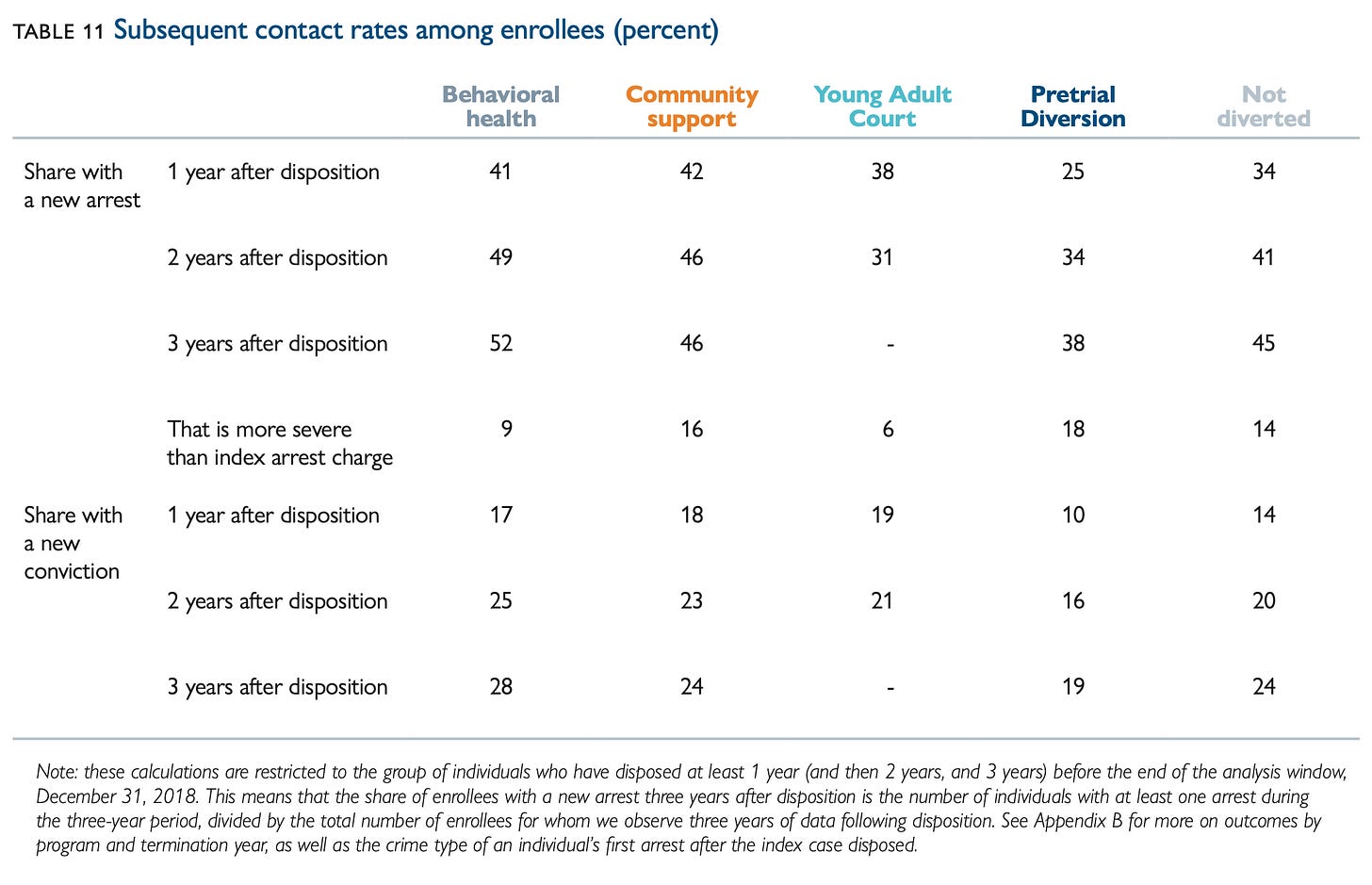

The study analyzed historical data in programs for felony offenders, including Behavioral Health, Community Support, and Young Adult courts. Table 11 of the study shows a pattern of higher arrest rates for those going through the collaborative courts than those who were not diverted at all. For example, 41% who went through behavioral health diversion had at least one new arrest after one year, 42% from Community Support Diversion had at least one new arrest, and 38% from Young Adult Court had at least one new arrest. These numbers compare unfavorably to the 34% figure for those defendants who had not been diverted. Three years after disposition, 52% from Behavior Health Court and 46% from Community Support Court had at least one new arrest. These numbers also exceed the 45% figure for those defendants who were never diverted.

If the purpose of diversion is reform, having higher or identical recidivism rates to those who are not diverted demonstrates that the program isn’t working. The recidivism rates for PTD participants with less serious misdemeanor offenses were better, with 25% picking up at least one new arrest after one year compared to 34% for those non-diverted, and 38% picking up at least one new arrest after three years compared to 45% for those non-diverted. While even low level PTD results were not stellar, at least they were in the right direction. Felony diversions, however, were heading in the wrong direction.

Exceptionally high number of new arrests during diversion found in all programs

The study also showed that diversion participants were committing an alarming number of new offenses even during the period in which they were enrolled in a diversion program. The authors wrote, “Defendants enrolled in Collaborative Court programs have more arrests during the pretrial period on average than defendants who are not diverted.” Table 10 of the study reveals that defendants who had been diverted multiple times to Behavioral Health Court were averaging 3.9 new arrests during the program. In Community Support Court, single referrals averaged 3.1 new arrests, while those referred multiple times were averaging 4.4 new arrests.

Even lower-level offenders in the original PTD program who were given multiple referrals averaged 4.4 new arrests while enrolled — seven times higher than those who received single referrals. The fact that diverted defendants were regularly allowed to commit three or four new crimes while out of custody raises serious public safety concerns.

Worsening attendance and success rates

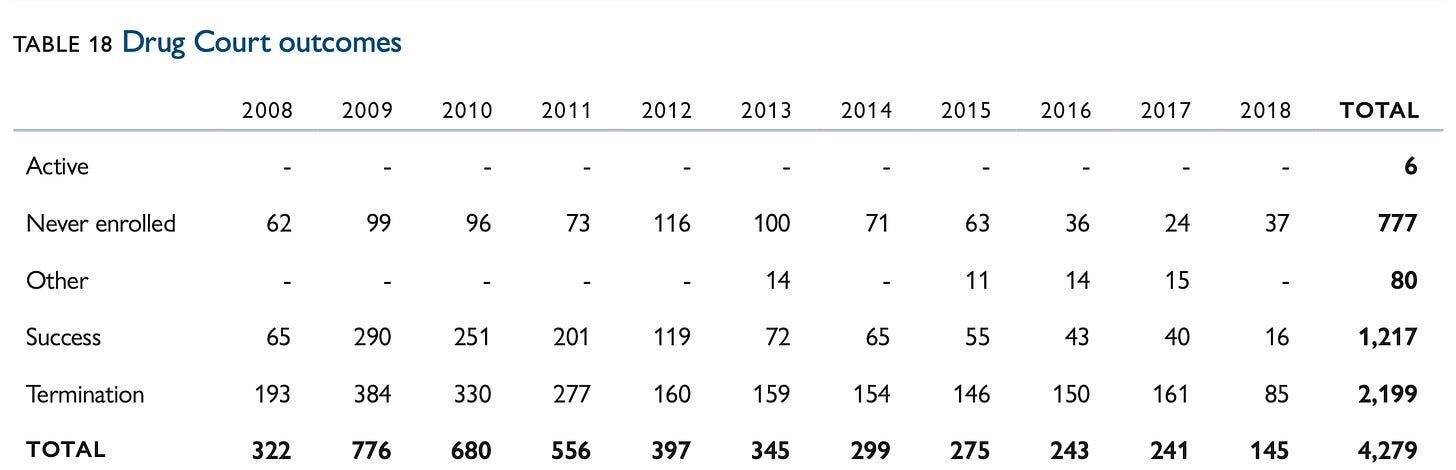

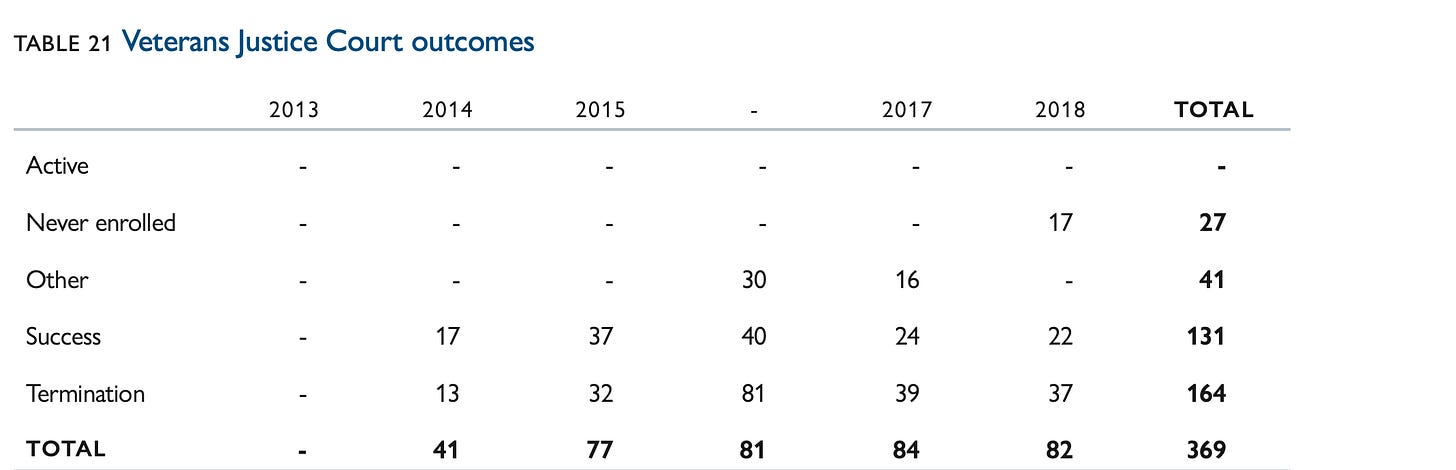

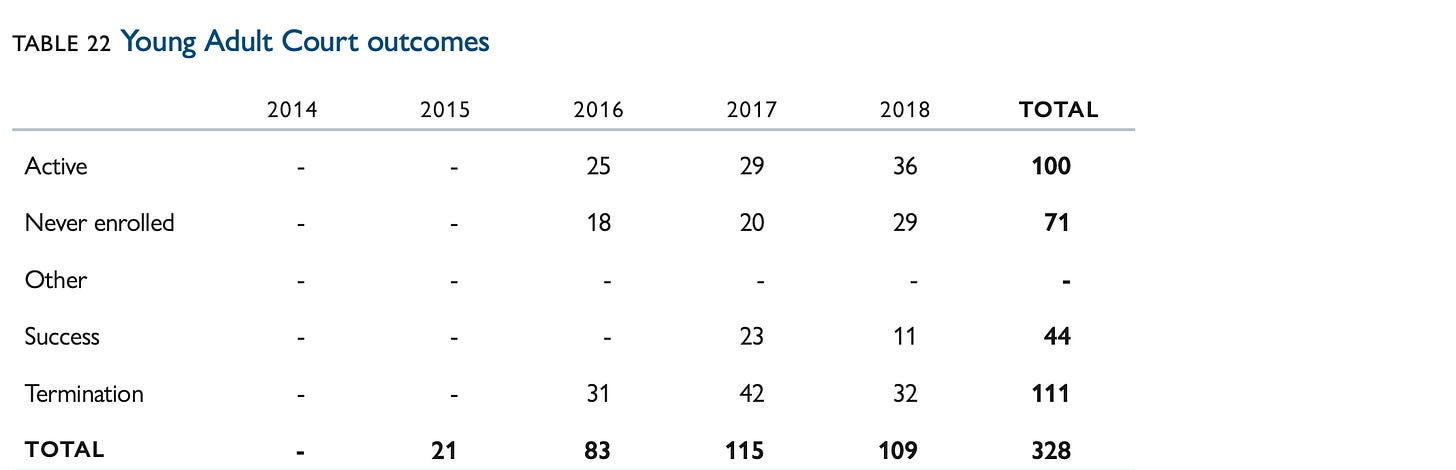

Tables 16 through 22 demonstrate the success and failure rates for the different programs, measured in terms of completion. Although the study barely discusses these findings, they show that many people referred to diversion either never showed up or failed to meet minimum enrollment standards. In addition, many were terminated by the Court.

Combining figures for non-enrollment and termination failures (and excluding active diversions) during the last year of the study (2018), the failure rate for Young Adult Court was 84%, for Veterans Justice Court 66%, for Misdemeanor Behavioral Health Court 79%, for Drug Court 84%, for Community Justice Center 83%, and for Felony Behavioral Health Court 89%. Even the failure rate for the more successful low-level offender PTD increased steadily, from a recorded low of 11% in 2009 to a high of 51% in 2018.

In conclusion, the authors say, “This report demonstrates that many of San Francisco’s diversion programs target a high-risk sub-group of the justice-involved population. Participants in these programs experience lower conviction rates than non-diverted counterparts, on average, but continue to have high rates of contact with the criminal justice system — both during and following diversion.”

Stating that participants in diversion had “lower conviction rates” simply means charges were dismissed for those who made it through the program. In theory, these dismissals were a reward, while withholding dismissals for failed participants was meant as a deterrent. “Public defenders could say, ‘Here’s your only chance. If you screw it up, you’re going to jail,’” one former attorney explained.

The numbers in the study suggest that while this approach may have worked for low-level offenders given one chance at PTD, it was not an effective approach for the “high risk subgroups” enrolled in felony diversion or for those with multiple program referrals. Defendants who committed more serious offenses, the study says, continued to have “high rates of contact with the criminal justice system, both during and following diversion.”

Damage control after publication of July 2020 study

Data from the July 2020 study must have surprised and disappointed its authors and supporting institutions because, in June of 2021, without any additional historical data, CPL repurposed data from the 2020 study and released a working paper entitled “The Impact of Felony Diversion in San Francisco.”

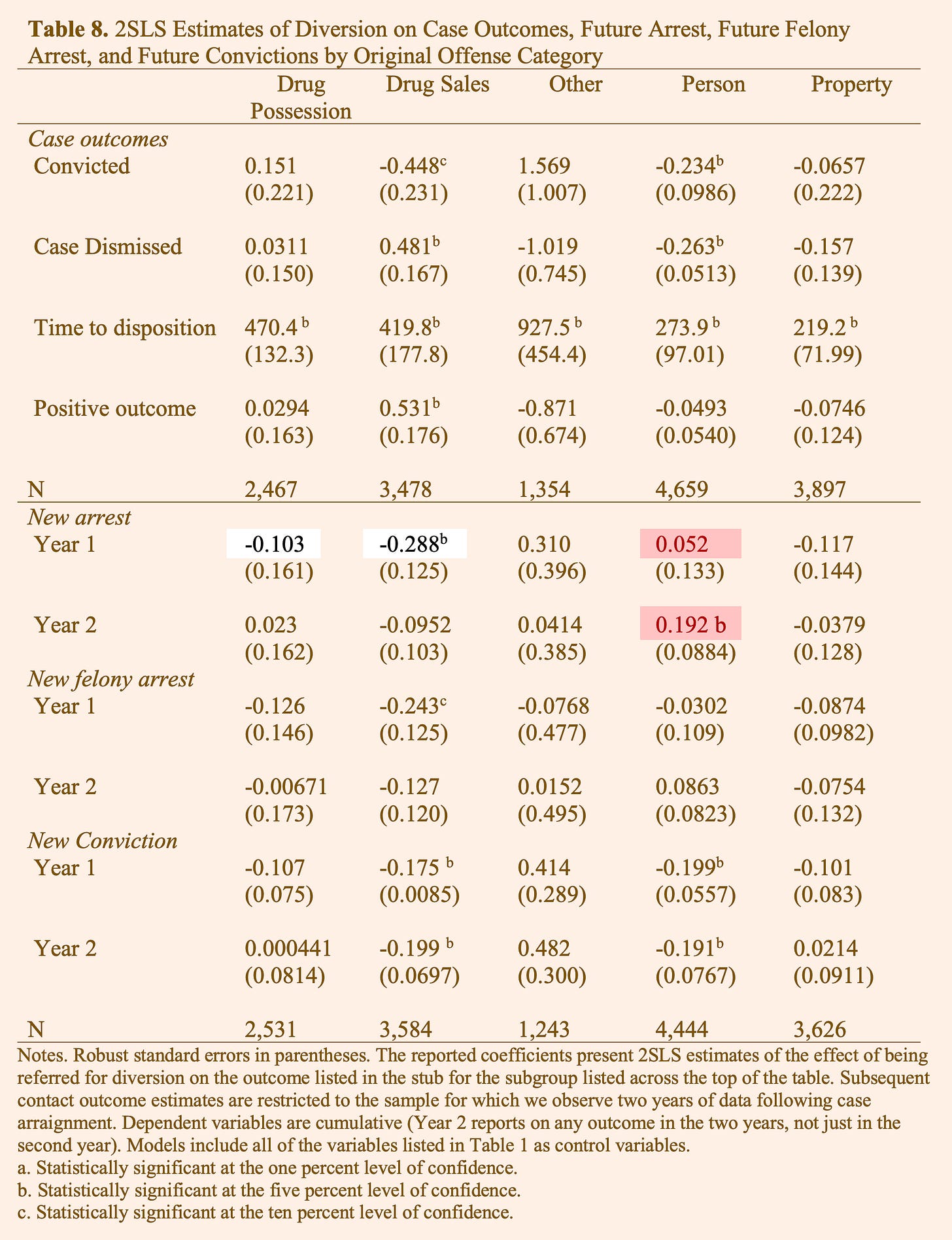

Unlike the original study, which used actual data and a straightforward methodology, the 2021 paper was like an Olive Garden never-ending word salad, stumping even some numbers experts. Our next step was asking a data scientist to review both studies. His conclusion was the authors resorted to using a “non-standard 2SLS methodology without justification” to explain away the June 2020 report, but “could not explain away all the problems identified in that original study.”

For example, on page 3 of the 2021 paper, the authors admit: “Regarding measures of future criminal involvement, simple comparisons of means as well as mean differences that regression adjust for observed personal and case characteristics generally show that those who are diverted are more likely to be arrested in the future, more likely to be arrested in the future for felonies, and more likely to experience new convictions.”

At page 25: “We see even larger estimated effects of diversion on cumulative arrests through the second year, with the diverted seven percentage points more likely to be arrested and eight percentage points more likely to experience a felony arrest relative to those who are not diverted.”

In a May 5 2022 article, SFGate reporter Eric Ting cites the 2021 working paper in support of Boudin’s unprecedented expansion of diversion programs. “Boudin’s office argues that diversion leads to lower rates of recidivism than conviction and incarceration. A California Policy Lab report from 2021 found that individuals going through diversion were 10% less likely to be arrested for drug possession and 28% less likely to be arrested for drug sales after one year than were individuals convicted and incarcerated,” Ting writes. It appears Boudin cherry-picked the most impressive sounding data for Ting, but both apparently ignored the rest of the study. The chart Ting drew his numbers from shows persons diverted were 5% more likely to be arrested for crimes against a person after year one, and 19% more likely to be arrested for crimes against a person after year two, than individuals convicted and incarcerated. (“Crimes against a person” include assaults, robberies, and other violent offenses.) But more importantly, these figures from the 2021 working paper are only “estimates” using a non-standard methodology, and these estimates do not match up to the actual results reported in the 2020 study, which cites failures across the board for felony diversion programs through the same study period (See Table 11 above). The study also does not explain the high numbers of new arrests while defendants were in the programs.

Despite these findings from the 2021 paper, Boudin dramatically increased diversion referrals for crimes against a person — assault cases diverted by Boudin increased by 338% vs. his predecessors, and robbery cases diverted by Boudin increased 244% vs. his predecessors. If Boudin is relying on the 2021 paper, which shows diverted participants had a 19% increase in arrests after two years, he shouldn’t have been sending violent crimes to diversion at all. And the failure rates in both studies should have indicated the need to pause and fix the problems, not exponentially increase referrals.

Patrick Thompson attacked a cop with an axe, ‘successfully completed’ diversion, then stabbed two women

In an effort to understand the justice system, several community groups sponsored a three-part series over Zoom. Parts one and two included ardent Boudin supporter Lara Bazelon and other representatives from the San Francisco District Attorney’s Office, along with criminal justice experts from around the state. For the third part, which took place April 23, 2022, Boudin and former assistant district attorney Brooke Jenkins were invited to speak. Boudin was a no-show.

Jenkins, a top prosecutor in Boudin’s office, left her job to join the effort to recall her former boss in the upcoming June 7 election, along with veteran prosecutor Don Du Bain. Both Jenkins and Du Bain believe Boudin’s policies are dangerous. "Chesa has a radical approach that involves not charging crime in the first place and simply releasing individuals with no rehabilitation and putting them in positions where they are simply more likely to reoffend," Jenkins said. "Being an African-American and Latino woman, I would wholeheartedly agree that the criminal justice system needs a lot of work, but when you are a district attorney, your job is to have balance."

Jenkins points out that two-thirds of Boudin’s office is now managed by former public defenders, including the Collaborative Court Unit. “That person did away completely with every single criteria that we had for how someone was eligible for these court programs and whether or not they could stay if they reoffended while they were out, or didn’t show up and do what they were supposed to do.”

On Twitter Jenkins was even more blunt: “Chesa Boudin does not hold criminal offenders accountable and now the data proves that … Conviction rates have plummeted. His diversion rates have skyrocketed but what most don’t know is that he is abusing those programs, which explains why they aren’t working … He has removed all criteria and guidelines for these programs, granting dismissals to those who continue to offend and fail to adhere to program requirements. His abuse of these programs undermines their effectiveness.”

There is no better example of what Jenkins says than the Patrick Thompson story. Thompson had been charged with three separate cases in 2017: misdemeanor contempt of court order, felony assault with a deadly weapon other than a firearm and battery, and felony battery with serious bodily injury. A judge declared him incompetent, and he was transferred to Napa State Hospital for the mentally ill. After his release, he was accepted into San Francisco’s Mental Health Diversion program, which the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office said he “successfully completed” in August 2020. A court transcript shows that the DA’s office didn’t object to Thompson’s release, despite the fact he had been arrested five months prior — while still in the diversion program — for threatening a female police officer with an axe. "If it was up to me, I'd kill everything that stands,” Thompson said. Then, on May 4, 2021, after he was deemed a “successful” diversion graduate, Thompson randomly stabbed two women, ages 63 and an 84, multiple times (fortunately, they survived).

Boudin hasn’t tracked diversion programs since taking office

On March 4, 2022, under pressure from pro-recall advocates and the press, Boudin released data on his “charging rates and case outcomes” directly to Susie Neilson, a data reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle. Neilson said the numbers showed Boudin “has sent a greater percentage of defendants in robbery, assault and drug cases to diversion programs than his predecessor [George Gascon], while obtaining convictions in a smaller share of those cases.” What Neilson neglects to mention is the reason for the lack of convictions: Boudin grants dismissals even to those who reoffend, meaning cases languish for months, even years, while defendants are given multiple diversion program referrals.

The victim advocacy and public safety group Stop Crime SF, one of many organizations that had been requesting detailed data regarding Boudin’s diversion tactics to no avail, finally hired renowned First Amendment attorney Karl Olsen to make a Public Records Request on their behalf. On April 6, 2022, Olsen wrote to Boudin’s office asking for “case numbers, original filed charges, original filing date; records of subsequent arrests or convictions involving the defendants in these cases after diversion … Records showing failures to attend or enroll; Records of multiple diversion referrals involving the same defendant; and record of defendants being terminated either by the Court or a defendant voluntarily removing himself from the program.”

Attorney Nikki Moore, recently hired as Boudin’s public records and transparency expert, responded to Olsen’s request on April 15, 2022. Shockingly, despite his claim of reducing recidivism through diversion, Boudin doesn’t have any records to back it up. “Our office has been working hard to compile diversion data for disclosure to the public,” Moore writes. “We have dedicated substantial staff resources, including one person working full time since October to obtain, clean, and standardize diversion data from the agencies that collect it, and match it to the SFDA data on arrests filings, and case resolutions.” Moore tells Olsen the office anticipates the data will be ready for release by May 11, 2022, but “reserves the right to extend the time of our estimated date of disclosure.”

Then Moore drops an additional bombshell: “Our figures are ‘case level’ specific, not ‘person specific,’ and as such, we cannot look at subsequent contact of the same person without conducting additional analysis.” In other words, if a defendant is arrested for 10 burglary cases while in diversion and 10 burglary cases after diversion, Boudin can’t trace those 20 burglaries back to that individual. Without “person specific” data to track defendants with multiple cases, Boudin’s recidivism figures will be both understated and unreliable.

The success rate of Pretrial Diversion, even with low-level offenders, has been on a steady decline for nearly a decade. Two studies, both done by a progressive think tank and funded in part by the pro-diversion Arnold Ventures, show programs failing even before Chesa Boudin became district attorney. Brooke Jenkins, a former prosecutor from Boudin’s office, said Boudin’s diversion expansion includes the removal of safeguards and standards designed to protect the public, which she characterized as an abuse of diversion programs.

When a violent, repeat offender like Patrick Thompson is allowed to stay in diversion after attacking a police officer with an axe and saying he wanted to “kill everything that stands,” and, just months after “successfully” completing the program, randomly stabs two women multiple times, it’s hard not to agree with Jenkins. As if that isn’t troubling enough, in the two-plus years Boudin has been in office, he hasn’t monitored any of the diversion programs and is now “in the process” of gathering the data under threat of legal action.

Even if Boudin is able to cobble something together, it won’t include the “individual specific” information essential to analyzing recidivism and the success or failure of diversion programs. For two years, Boudin had the ability to track diverted individuals and their recidivism, yet his office says they “cannot look at subsequent contact of the same person without conducting additional analysis.” For Boudin, diversion has been a reckless social experiment to appease his ideological belief that no one should be incarcerated — no matter how dangerous they are or how many people they put at risk. If the programs are failing, Boudin doesn’t want to know about it — and he doesn’t want you to know about it either.

THE STUDIES:

July 2020, California Policy Lab, Alternatives to Prosecution: San Francisco’s Collaborative Courts and Pretrial Diversion

June 2021, California Policy Lab, The Impact of Felony Diversion in San Francisco

Bravo, Susan. This has to be what finally solidifies the recall of our inept DA.